Click here to read the full story from ATA

As post-pandemic supply-chain challenges have been thrust into the public consciousness, a new class of armchair experts has risen to explain all that ails America’s trucking industry. Bureaucrats, essayists, and other cultural commentators—most of who have no real-world experience in trucking—are quick to explain why, for example, the industry faces a labor shortage as it strives to hire the next generation of professional drivers. They almost always point to high turnover rates as the empirical epicenter of trucking’s labor woes.

Case in point: This recent New York Times essay, which oddly pinballs between saying the job is too dangerous on one hand, but that lifesaving technology is too Orwellian on the other hand. But setting these rhetorical contortions aside, the author also claims to have struck the nail on the head when it comes to driver turnover rates:

For decades, truckers have quit at alarming rates, leading to a chronic shortage. The turnover rate was at a staggering 91 percent in 2019, which means that for every 100 people who signed up to drive, 91 walked out the door. Plenty of people have the commercial driver’s licenses needed to operate trucks, said Michael Belzer, a Wayne State University economist who has studied the industry for 30 years. “None of them will work for these wages,” he added.

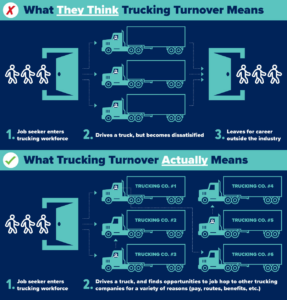

The problem? The author, Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein, fundamentally misunderstands what the annual truckload driver turnover rate measures. He, and many others before him, assume or imply the rate captures drivers leaving the industry and often cite poor pay or working conditions as the cause. That is wrong. If 91% percent of truck drivers were quitting the industry within a year, our economy would have collapsed a long time ago.

Turnover is not an indicator of people exiting the industry (we know, because ATA created and tabulated the metric). Rather, it more accurately measures drivers moving between carriers. It captures churn within the industry—not attrition from the industry. While retirements and exits account for a small percentage of turnover, by-in-large that is not what this figure is counting.

So why are drivers moving between fleets in such great numbers and frequency? There are many factors at play, but 1) demand and 2) opportunity are salient.

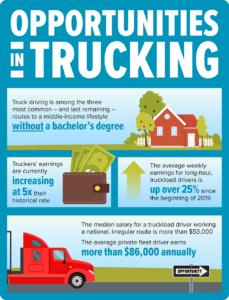

Trucking is an extremely tight labor market, for cyclical and structural reasons. Drivers are in high demand today—a fact exacerbated by COVID. To attract and retain drivers, fleets must increase pay, which is now happening at extraordinary levels. We’re witnessing unprecedented pay increases across the industry, with weekly driver earnings surging at a rate more than 5x their historical average—up more than 25% for long-haul, truckload drivers since the beginning of 2019. Fleets are also offering sizable, five-figure sign-on bonuses and full benefits as they all compete for the same limited pool of drivers.

- Business Insider | One of the largest trucking companies in the US is giving raises of up to 33%, allowing drivers to make up to $150,000 in their first year, amid worker shortage

- Transport Topics | More Carriers Raise Pay Amid Driver Shortage

- CNN | Truckers are getting big pay hikes, but there’s still a shortage of drivers

- FreightWaves | Driver pay hikes not letting up

- FOX Business | Workers leaving jobs for trucking industry, six-figure salaries

What does this mean for “turnover”? Driver A, who’s been working for a fleet for only four months, knows he can jump to another carrier and get an immediate $15,000 sign-on bonus plus pay raise. Six months later, he can do the same thing again. This churn—or poaching, or whatever one wants to call it—is what inflates turnover in a tight labor market.

So when Kaiser-Schatzlein and others point to high turnover figures as a sign of truckers’ job dissatisfaction, they’re missing the mark. One could argue they’re getting it backwards. In many respects, high turnover is an indicator of driver empowerment. When the labor market tightens, drivers find themselves in the driver’s seat (pardon the pun), putting millions of hard-working men and women in control of their own destiny in ways they haven’t been in years, if ever.

Many are seizing those opportunities that a booming freight economy present by moving to different companies for higher pay rates, bonuses, new routes or better benefits. No one can blame them, nor can anyone blame motor carriers who are competing vigorously with one another to hire good drivers and keep the ones they have.

The fact is truck driving remains one of the steadiest paths to the middle class without requiring a costly, four-year college degree. It cannot be off-shored, and its essentiality to our way of life and standard of living continue to grow over time. Kaiser-Schatzlein says high turnover exposes truck driving as a dystopian nightmare. For the millions of Americans who chose this profession, the ability to provide for their families without the burden of student loan debt is far from dystopian—it’s the American Dream.